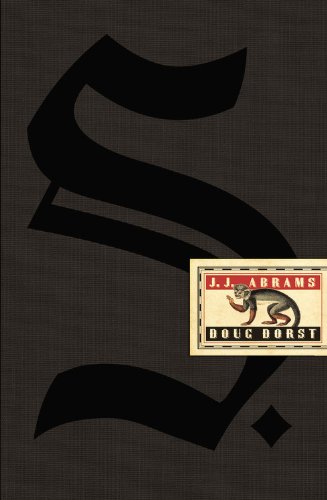

Books are supposed to be interactive, am I right? The connection between reader and author should be a dynamic experience. Both are creators of meaning. That being said, I was initially excited to get my hands on Ship of Theseus (or, simply, S) by Doug Dorst (in collaboration with J.J. Abrams—yes, he of Lost, Alias, and the Star Trek reboot), as I had heard that, as a reader (and an English major in college), I would, quote unquote, get it.

The conceit of this tome is that we, the reader, have stumbled across a library book (the edition has everything you could possibly find in a library book: Library of Congress markings, library stickers, etc. to aid in the verisimilitude). Within the covers we find the work of reclusive and mysterious author V. M. Straka, who has written the epic journey of protagonist “S.” Why just “S”? Well, he has no memory of the past, and the novel is his odyssey toward both identity and a mysterious woman who’s haunting his reality. There is more to this adventure, however, because we are also privy to the annotations of two people who occupy the “real world,” as it were: Eric, a grad student working secretly at the library in order to debunk his obnoxious professor’s theories about the author of SoT (as the annotators keep referring to it), and Jen, a part-time undergrad librarian, whom he meets within the pages of the book in the form of written communications across the pages. Their story plays out alongside the main narrative of the book, and the two worlds connect thematically as these two doodling protagonists also embark on a journey of self-discovery.

Now, while all this sounds unique and adventurous and artfully clever, the result comes across as frustrating more than ingenious. The central story of the book, that of S’s odyssey, is just not that interesting. And, written as it is in a language so self-consciously “symbolic” (the two students attempt to connect the content of the narrative to the author’s life, decoding meaning and making leaps with the interpretation), it comes across at times like literary masturbation (without the happy ending—and by this I mean sensory and literary satisfaction—of, say, a Virginia Woolf or a Milan Kundera).

The margin annotations themselves are also not in chronological order, as our two scribblers refer to events and episodes that have not even happened to them yet, and the reference only makes sense further down the line. I found myself going back several times to make sure I didn’t actually miss something as I was reading, thus breaking the rhythm of both stories. All of the artifacts inserted into pages (newspaper clippings, postcards, photos, etc.) are, at first, an interesting addition to this experiment, but they eventually become little more than a nuisance, as they slide out onto the bed, or the floor, or the dinner table—and you’d better remember which section they came from. And don’t get me started on the footnotes. My understanding of this non-linear narrative (at least in Jen and Eric’s case) is that they have already finished the book and are now going back through the novel, passing messages to each other on pages where they first started their flirtation and love affair. That’s all well and good, but nothing of great interest really happens in this narrative line, either. There’s some mystery about a secret society (known as “S”—surprise, surprise) that may be sending them warnings to stay away from their line of research, but there is no sense of urgency to the threats.

SoT is a search for meaning—academically, spiritually, and personally. The literal search is manifested in the interrogation of the text and also in the research going on beyond the page as Jen and Eric attempt to connect the clues left by Straka (who may not even be the author of the book) and his translator. However, stakes are just not that high: a relationship? A career? A life? Only two scholars could have this much enthusiasm for a text this mundane. The book definitely has a Möbius strip quality to its narrative and initially feels like a clever novelty, but the novelty runs very thin very quickly. Unlike a grad student who’s working on solving the puzzle of one book, I don’t have time to go back and re-read, then re-read again, as some have suggested the reader do. My reading life is too short to waste on a journey this murky and pretentious. I have no doubt that I am ultimately missing the point of this literary masterpiece and its labyrinthine narrative. Academics may someday write whole dissertations on the narrative complexity of Dorst and Abrams’s novel, and I will be the clueless philistine. But, as with Lost (and its winding storylines), by halfway through, I really didn’t give a shite.

Wait…I’ve figured out what the S means.